One of the first things I was introduced to in philosophy was the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning will tell you why, if all puffins are birds, and what you can see in front of you is a puffin, that what you see in front of you is a bird. Inductive reasoning lets you know that if the sun has risen every day of your life so far, you can be fairly certain the sun will rise again tomorrow.

The insurance industry trades in inductive reasoning about risk. Their model is simple maths. If with all things taken together (a), some amount of people will incur damages (b), insurers will charge in premiums (c) – to cover the damages with payouts (d), and keep the remainder to invest (e) and/or keep as profits (f).

Insurers would like to be recognised as a benevolent industry of protection, society’s safety net. They will tell you their purpose is to: “be with you today, for a better tomorrow” (Aviva), “act for human progress by protecting what matters” (AXA), and “share risk to create a better world” (Lloyd’s).

You therefore might imagine that if insurers realised fifty years ago that the maths of their model was going to shift, they might make some changes. Knowing that climate change would drastically increase damages (b) and therefore payouts (d), they definitely wouldn’t underwrite insurance for fossil fuel expansion (c) for one, or invest their money into fossil fuel companies (e) for two.

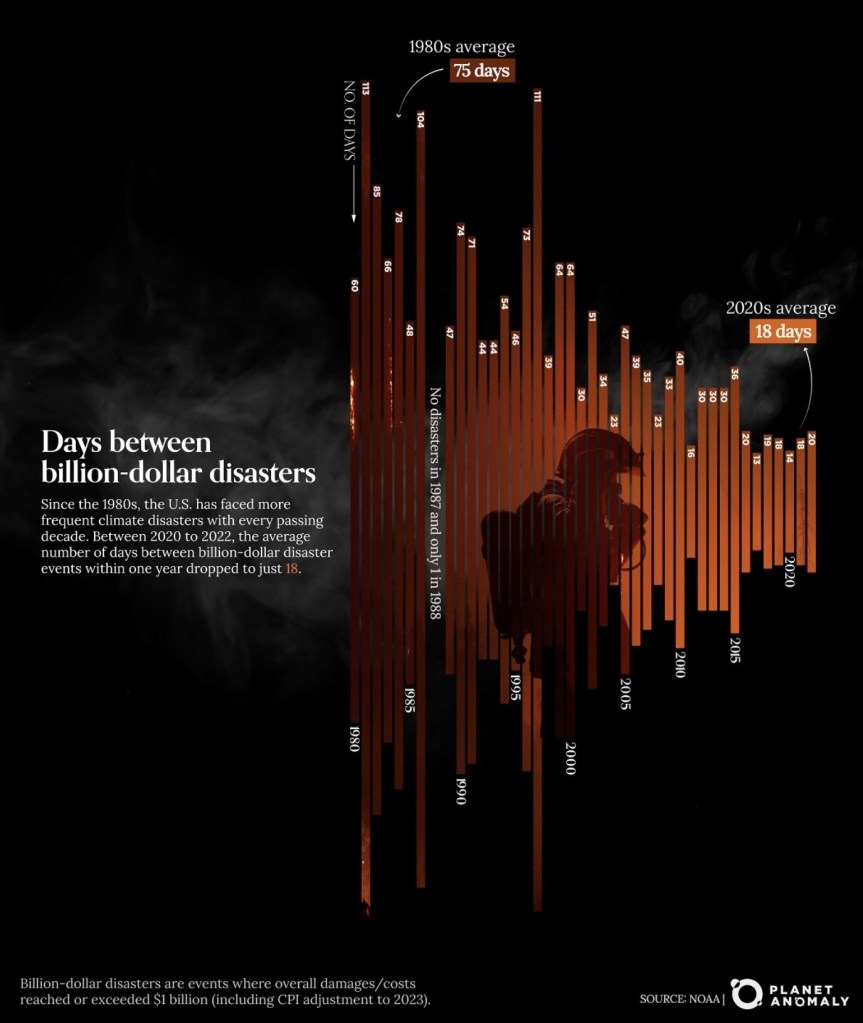

Except, despite it being 50 years since Munich Re first sounded the alarm about how climate change would affect the industry, we’re here. 2023 is now almost certain to be the hottest year in human history, and as a result, the time between the most costly billion-dollar disasters is rapidly decreasing.

Rather than change their underwriting and investment policies, insurers have chosen another route. What’s easier than changing their model of operation? Easy – shrinking the scope of what they are prepared to cover.

What happens in a region where climate-related damages (d) are so high that it becomes impossible for an insurer to affordably charge for premiums (c) in such a way that maintains profits (f)? The insurer doesn’t shoulder the responsibility and risk and balance it against its other costs. It simply pulls out of the market.

This is where we find ourselves now. In the US there has been a rapid increase of people who are underinsured, uninsured or uninsurable. Louisiana, Florida and California are all facing an uninsurability crisis.

Of course, uninsurability doesn’t eliminate the existence of risks, it simply transfers it. No longer on the balance sheets of the insurers, risks instead become the stories of people’s personal bankruptcies. And when the consequences of this becomes intolerable, the state steps in. In the US, the government has variously stepped in via schemes such as the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The risk is now societal.

And yet, at the same time as the US government is left picking up the mounting costs of climate losses, insurers are able to still cream profits off of areas where there remains profit to be made – even (!) as they continue to insure the fossil fuel industry.

This symptomatic of a wider pattern in our societal risk management: while profits stay private, losses become public.

This pattern is in part due to our over-dependence on a debt-driven economy. While insurers finance fire, we are collectively financing FIRE: finance disproportionately goes into Finance, Insurance and Real Estate, rather than into productive uses. Such is the extent of this – in the UK, a mere 10% of bank lending helps non-financial firms; the rest is FIRE (Mariana Mazzacuto) – that we end up with a financial system where actors become “too big to fail” and act with an implicit government guarantee. With this comes the same transference of risk: from private to public.

This transference of risk is regrettable in its own right; it is downright dangerous in such a situation where the inductive reasoning of a stable climate is no longer dependable. In the AXA Future Risks report 2023, climate change comes out as the number one risk according to both experts and the general public, in all geographical areas. We have entered into a new domain of risk in which what we knew about yesterday can no longer guide what we can ascertain about tomorrow.

Our financial system is not built to optimise for public goods, but for private wealth. As a consequence, when business as usual threatens public goods, rather than change the model of the financial system, financial actors continue to gamble on private wealth even as the stakes become ever higher.

This is how insurers can declare their intentions for public good even as they act to undermine it.

Aviva will be with you today, for a better [FTSE 100 listing] tomorrow. AXA will act for human progress by protecting what matters [to its shareholders]. Lloyd’s of London will share risk to create a better world [for its syndicates].

Further Reading:

Fifty Years of Climate Failure: 2023 Scorecard on Insurance, Fossil Fuels and the Climate Emergency